When just floating peacefully in the water with their brood mates, the Culex mosquito larvae in the image above does not look very frightening. But in their adult form, they are the prime vector for spreading West Nile virus — a sometimes mild, sometimes fatal disease.

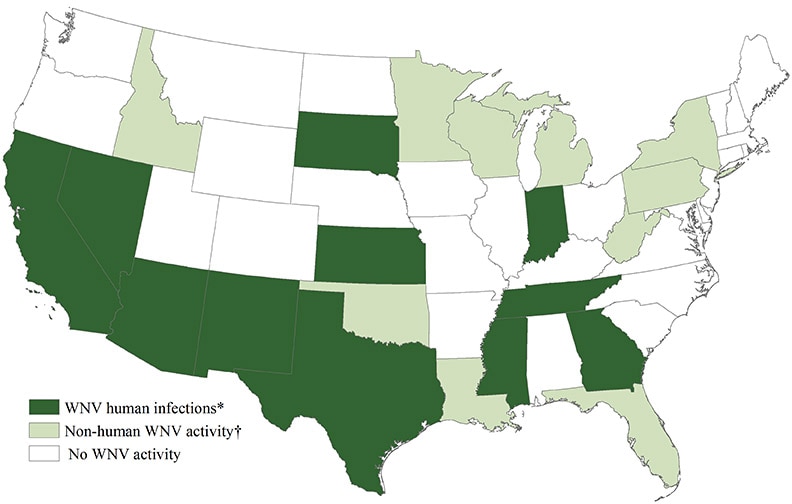

Part of the Flavivirus family, which includes Dengue, Zika, and yellow fever, West Nile virus migrated with birds from Uganda in the 1930s to Europe, and then into the Americas in 1999. An invasive microbe, West Nile virus has now spread from shore to shore, with 2,038 cases reported across 47 states in the US in 2016.

Forty-seven states have confirmed human cases of West Nile virus or blood donors who got a positive screening test for it but have not necessarily been confirmed.

Globally, the World Health Organization notes that about 80% of people infected with West Nile virus will suffer no symptoms at all, so it's likely much more widespread than even these numbers indicate.

Of the confirmed cases in the US in 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says about 44% had a non-neuroinvasive form of complications, which includes fever, weakness, and aches.

Fifty-six percent (1,140) developed neuroinvasive infections, including encephalitis or meningitis, which can quickly become life-threatening. Only about 1% of total West Nile infections develop into the more dangerous neuroinvasive illness, according to the CDC, so the total number of infections could be ten times that, which would help explain how the disease has spread so far.

Incidence of neuroinvasive cases of West Nile virus in the US, as of January, 2017, the number is out of 100,000.

Worse yet, recent studies appear to indicate that people who are infected with a Flavivirus (West Nile or Dengue) could suffer a more serious infection if they are later exposed to the Zika virus.

Research conducted with mice and mosquitoes by the CDC in late 2016 did not find Culex species mosquitoes were "competent vectors" of the Zika virus. A study published slightly later in Emerging Microbes and Infections found a member of the family of Culex species could infect mice with the Zika virus. More studies are needed to suss out the truth.

With relentless warming temperatures in the US and the expanding habitats of mosquitoes, the eventual range of Zika in this country remains unknown. In some parts of the US, spring and summer are about to arrive. In others, mosquitoes are active all year. If you feel ill after a mosquito bite, it is important to get a heads-up on symptoms that could be serious.

Signs & Symptoms of West Nile Virus

Mosquitoes are out at dawn, dusk, and in the shade and shadows during midday. Damp ground and water attract mosquitoes, and Culex mosquitoes lay their eggs in rafts of about 200 on stagnant, slow-flowing water. Residual water in old tires, bird baths, children's toys, and many other containers make ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes. Most cases of West Nile virus are diagnosed in the summer months between June and September.

While the most severe complications of West Nile pass most infected people by, you should take notice if you develop symptoms after a mosquito bite. The incubation period from bite to developing symptoms is between two and 14 days.

Whether you went on a camping trip and got munched by your mosquitoes, or you were out early in your yard one morning, West Nile virus could cause mild flu-like symptoms, but worrisome signs that warrant a trip or call to your doctor include:

- severe headache

- fever

- rash

- diarrhea

- stiffness in the neck

- seizures

- disorientation

Only about one in five people experience symptoms of West Nile virus. West Nile virus is diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentation of symptoms, and the laboratory identification of antibodies in body fluids like spinal fluid or blood. The greater your exposure to mosquitoes through outdoor work or play, the greater your likelihood of contracting West Nile virus from an infected mosquito.

Persons over age 60, those with compromised immune systems, or who suffer chronic illness are at greater risk for the neuroinvasive form of West Nile virus. At present, the only treatment for severe West Nile infection is supportive care.

Neuroinvasive infections linked to West Nile virus take the form of encephalitis or meningitis. Caused by the virus that causes West Nile virus, encephalitis is an inflammation of the brain and surrounding tissues, while meningitis is inflammation of the tissue near and around the spinal cord. The recovery period from these infections can be lengthy, and some disabilities may be permanent.

Mosquitoes feed at different times

There is currently no vaccine against West Nile, Zika, or Dengue fever. In February, the National Institutes of Health initiated an experimental study of a vaccine that targets the response of the human body to mosquito saliva instead of a particular pathogen. Researchers hope an allergic reaction to the saliva will ramp up the immune system, and block infection by the pathogens that cause West Nile, malaria, Zika, and Dengue fever.

In the meantime, throughout the United States, you could already have been exposed or could be exposed to West Nile virus through a mosquito bite. Chances are good that if you have been infected with West Nile virus, you may never know about it. In areas where Zika is active, prior infection with West Nile could cause a more severe infection. That means taking precautions against infection by Zika extra important.

Protect yourself with clothing and a repellent containing DEET if you must be out when mosquitoes are most likely to be biting. If you notice a couple of mosquito bites and begin feeling poorly within a week or so, take note of your symptoms and call your doctor for advice.

- Follow Invisiverse on Facebook and Twitter

- Follow WonderHowTo on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+

Cover image by James Gathany/CDC

Comments

Be the first, drop a comment!