A recent study offers information that might help combat a deadly virus that affects an estimated 300,000 people each year in West Africa.

In late June of this year, the World Health Organization reported an outbreak of Lassa fever with 501 confirmed cases and 104 deaths. The virus, named for the Nigerian town in which it was discovered in 1969, kills approximately 5,000 people per year. While the virus is not endemic to the US, but occasionally travelers return with the virus, as happened in 2015. In that case, doctors diagnosed a sick returning traveler with a viral hemorrhagic fever and transferred to a specialized hospital facility where he passed away within four days.

What Is Lassa Fever?

Viral hemorrhagic fevers, like Ebola, are ghastly infections. Lassa fever is a zoonotic hemorrhagic fever, spread by a large rodent native to Western Africa and other countries where the disease occurs. Like many other infections, many of those exposed have no symptoms. With the Lassa virus, about one in five infections will be serious — impacting the kidneys, liver, and spleen. About 15% of those with severe Lassa fever die.

The rodent, Mastomys natalensis, or the multimammate rat, is the animal host for the virus, a member of the viral family Arenaviridae. The rodent excretes virus in its urine. Because the rats make their homes around humans and areas of food storage, the level of transmission of the virus is high. If the virus is shed in living quarters or on and around food, it can be ingested or inhaled when dry and aerosolized, causing infection. Even sweeping a home can stir up infectious residue that causes deadly disease.

In addition to direct contact, Lassa virus can be spread through body fluids, for example, in healthcare settings where caregivers aren't using the appropriate personal protective equipment.

In humans, symptoms of the virus occur within about one to three weeks of exposure to the virus. While the infection can be mild with only fatigue, slight fever, and weakness, the more virulent form of the infection causes bleeding from the eyes, nose, or mouth, vomiting, swelling, and shock. Multi-organ failure can result — leading to death. For those who suffer either a mild or severe form of the disease, permanent deafness is a frequent result.

The disease is almost always serious for pregnant women in their third trimester, with 95% fatality rate for the unborn children. When spread outbreaks occur, like this year in Nigeria, the death rate can be as high as 50% for hospitalized patients with the virus.

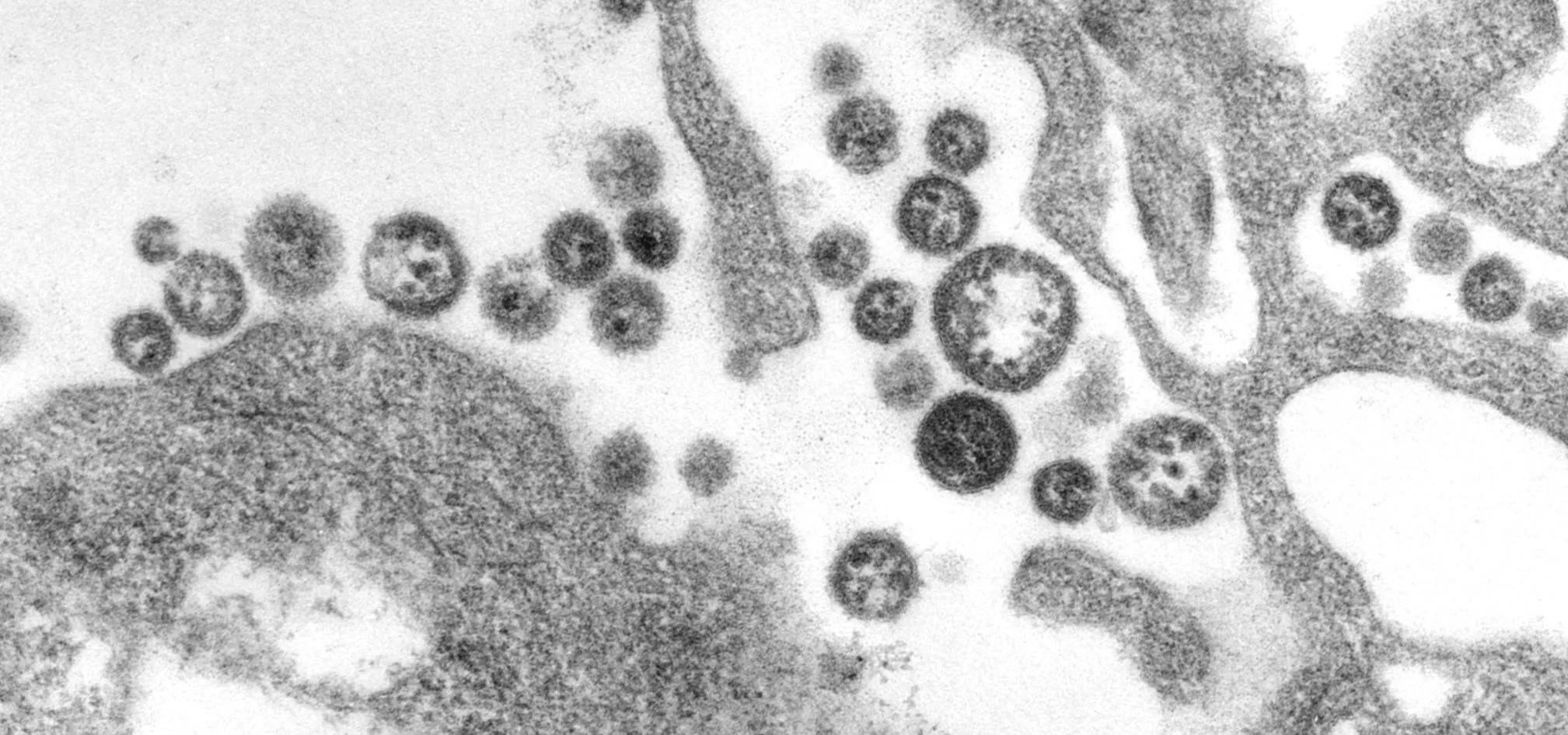

Three Lassa virus virions. The middle one has completely budded from its host cell.

New Research May Help Development of Vaccine Against Lassa Fever

In a study published in the journal Science, researchers from The Scripps Research Institute describe structural details of the Lassa fever virus that could help unlock therapies or a vaccine for the viral infection.

Despite the tens of thousands of people that die from Lassa fever each year, researchers had not cracked the puzzle of the structure of the virus that causes it. The first author of this study, Kathryn Hastie, worked for ten years on the problem, starting in 2007 when she was a graduate student at The Scripps Research Institute.

Because developing a vaccine requires understanding the structure of a microbe, Hastie had to study the protein that forms the arenavirus that causes Lassa fever in 3D using a technique called X-ray crystallography. The technique bounces X-rays off of the crystallized protein and works backward from where the X-rays landed to figure out the protein's shape.

When she had a model, Hastie looked at how human antibodies bound to the virus. The antibodies were from human survivors of Lassa fever, provided by the Kenema Government Hospital in Sierra Leone. The facility is the only hospital in the world that specifically treats hemorrhagic fever viruses.

Lassa virus capsid protein structure.

The image above reveals Hastie's work — a model of the Lassa virus protein that is bound to the (teal green) antibodies from a human survivor of the Lassa virus. This first view of the arenavirus, the research notes, "provides a much-needed template for vaccine design against these threats to global health." The authors also write the model developed by Hastie "provides the initial foundation for understanding the molecular mechanisms of neutralization of Lassa virus."

Despite the ten years needed to develop this model, this work could eventually contribute to saving tens of thousands of lives each year. In a press release Hastie said, "It was great to see exactly how Lassa was different from other viruses. It was a tremendous relief to finally have the structure."

- Follow Invisiverse on Facebook and Twitter

- Follow WonderHowTo on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+

Cover image by C. S. Goldsmith/CDC

Comments

Be the first, drop a comment!