Infections with group A streptococcus, like Streptococcus pyogenes, claim over a half million lives a year globally, with about 163,000 due to invasive strep infections, like flesh-eating necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

Distinctive substances on the bacterial surface, known as M proteins have been studied for nearly a century. After all those years of study, a team of scientists from the University of California at San Diego has discovered that these M proteins kill the immune system's white blood cells that try to destroy it, making M protein a major player in the virulence of the organism.

The death of these white cells, called macrophages, alerts other cells of the immune system to respond to the infection. However, if the infection becomes widespread throughout the body, inflammation caused by a rampant immune system response can aggravate tissue injury and create life-threatening conditions.

"So you can see this as a beneficial early warning system for infection, like Paul Revere riding out with a lantern to warn that the British are coming. The problem is that if a million people — or a million macrophages — light lanterns all at once and hay catches fire, then you're in trouble," Victor Nizet, study co-leader and researcher at UC San Diego, said in a press release.

The researchers published their report describing the role of M protein and macrophages in group A streptococcal infections on August 7 in Nature Microbiology.

Toxic Strep Infections

A few facts make group A strep infections particularly scary: infections seem to arise, appear in clusters or become widespread, then die out to a low prevalence; most people don't know how they became infected with strep; and the infections typically have a high mortality rate.

Before the advent of antibiotics, the late 1880s saw the death of 25–30% of children in New York, Chicago, and Norway from scarlet fever, an infection caused by group A strep and characterized by chills, vomiting, abdominal pain, and a red and bumpy rash. But, by 1900, the mortality rate in those locations dropped to less than two percent.

More recently, in 1987, a series of patients came down with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Their symptoms were infection with group A strep, shock (dangerously low blood pressure), kidney and multi-organ system dysfunction, and rapidly progressing soft-tissue destruction also known as necrotizing fasciitis. About 30% of these patients died, but that rate has been as high as 81% in subsequent clusters of streptococcal toxic shock infections.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a deep infection of the subcutaneous tissue below the skin. The infection destroys the fascia and fat, but may spare skin and muscle. The appearance of dead tissue that seems to be unstoppable has earned it the nickname of flesh-eating bacteria. Despite antibiotic treatment, and amputation to physically remove the infected tissue, about 27% of people with the infection die.

Some strep infections, like scarlet fever or strep throat, are spread by droplets from the mouth — so sneezing, coughing, and sharing drinking cups can also share the bacteria. Occasionally associated with a mild trauma of some kind, necrotizing fasciitis has also been seen more frequently in people with diabetes.

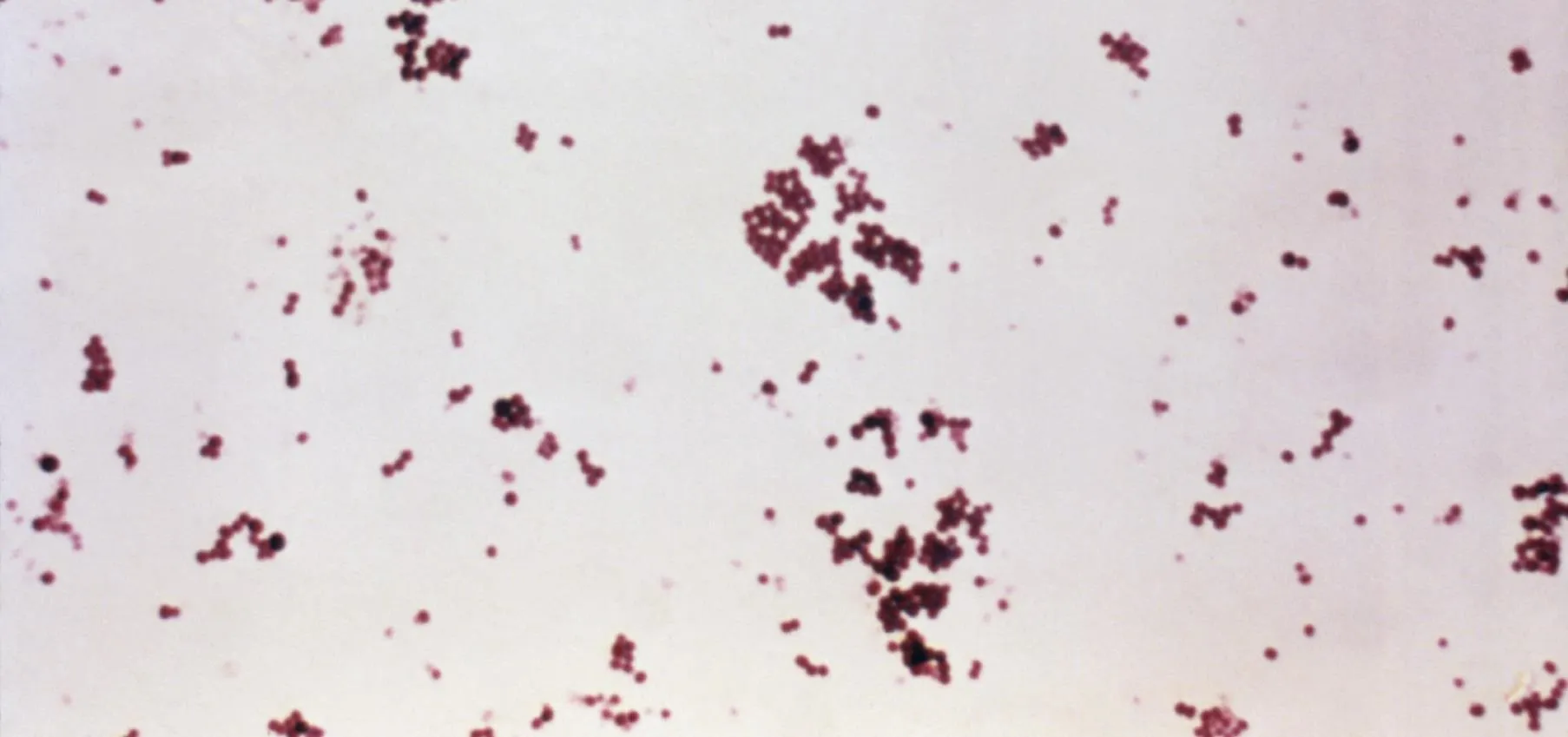

The common factor between these diseases is the severity of the infections and high mortality rates. M protein is an abundant molecule on the surface of some strains of disease-causing strep that researchers have described as looking like the "fuzz on a tennis ball" when viewed by electron microscopy. Strains of group A streptococci isolated from patients with invasive diseases have been mostly from M types 1 and 3 that produce potent fever-causing exotoxins A or B or both.

In addition to the exotoxins, the increased immune response that follows from macrophage activation by M protein during advanced stages of systemic infection with invasive group A strep can contribute to the severity of the infection and result in life-threatening problems.

The presence of M proteins on some strains of streptococcus has been known and studied for nearly 100 years, but the new research by Nizet and his colleagues describes its significance in invasive group A strep infections.

Old Finding Makes News Again

To figure out how M proteins affect the immune system the scientists mixed it with human macrophages in a test tube. They found a rapid destruction of the macrophages cell membrane and release of cellular components that increased in severity as the researchers added more M protein. Basically, the addition of M destroyed the macrophages.

In response to M protein, macrophages activated caspase-1-dependent NLRP3 inflammasomes, protein complexes in the macrophage's cytosol — the liquid inside the cell — that caused its death in an event called pyroptosis. Pyroptosis simultaneously kills the macrophage and starts a rapid inflammatory process by releasing a protein called interleukin-1 beta. Interleukin-1 beta signals other cells of the immune system to proliferate and come to the site of the infection and fight it.

Strep bacteria genetically engineered to lack M protein did not cause any of these effects in macrophages.

This is an electronic microscopy image of Group A Streptococcus (faint purple chains) overlaid with a confocal microscopy image of M protein (red) internalized in macrophages (blue).

Injection of mice intraperitoneally with M produced significantly more interleukin-1 beta than mice that received no M protein. The more M protein they received, the more interleukin-1 beta they generated.

Interleukin-1 beta release and macrophage death may contribute to an exaggerated inflammation that causes other devastating problems. For example, the inflammation in strep toxic shock syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis can cause leakiness of vessels that results in dangerously low, life-threatening blood pressure, a hallmark of toxic shock syndrome.

The new research has illuminated a process that might be used to help control invasive strep infections. Nizet and Valderrama have genetically modified macrophages in an attempt to figure out how to make them resistant to M protein-induced suicide and to identify potential therapeutic targets for invasive strep infections. M protein could be used as a vaccine target, but antibodies raised to it may also react with some human tissue, so UC San Diego and other researchers are trying to develop an M protein that wouldn't cause such a reaction and would be safe to use in vaccinations.

"Our study suggests that targeting M proteins with vaccines or antibodies or blocking the way macrophages bring it into the cell might prove clinically useful in cases where hyper-inflammation has become a problem, such as in an invasive infection or toxic shock syndrome," study researcher J. Andrés Valderrama said in a press release. "But it's a delicate balance — we don't want to block the early warning signal altogether, or the immune system would lose its first line of defense against strep."

- Follow Invisiverse on Facebook and Twitter

- Follow WonderHowTo on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+

Cover image via CDC

Comments

Be the first, drop a comment!