Ecosystem changes caused by agricultural choices in Brazil are creating a dangerous microbe mix in exploding populations of vampire bats and feral pigs.

Even as human-influenced climate warming is tipping the tables on ecosystems around the world, choices made by landowners in the Americas, from Mexico to Argentina, are setting the stage for emergence of diseases dangerous to humans and animals. These changes are bringing together two species notorious for spreading disease: bats and pigs.

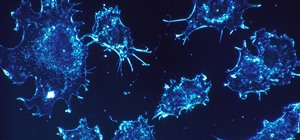

Vampire bats, because they feed only on blood, give all other bats a bad name. Of about 1,200 bat species, only three are bloodsuckers. Bats themselves are invaluable members of our world, but are known reservoirs of diseases including rabies, coronavirus, adenovirus, and hantavirus.

As very small mammals, bats are more similar to humans than to rodents like mice. They share food with other bats in need, and can live upwards of 40 years. Bats are important to pollination, and critical for keeping insect populations under control. A single brown bat can consume up to a 1,000 mosquitoes per hour, while the bats at Bracken Cave in Texas, which number upwards of 15 million, gobble somewhere around 250 tons of insects each summer night.

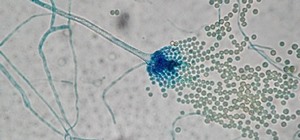

Vampire bats don't currently live in the United States, instead preferring the tropics of South and Central America, as well as Mexico. In a recent study published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, scientists focused on Desmodus rotundus, one of the three species of vampire bats. Environmental changes have boosted its numbers and the availability of its favorite food source—feral pigs—one of which is being fed on by two little bats in the video below.

Researchers at the Bioscience Institute at Sao Paulo State University in Rio Claro, Brazil, found that this population increase has also led to an alarming rise in the number of vampire bats feeding on feral pigs and wild boars, putting the two on a collision path for disease emergence.

As locals in the region cleared the land for ranching, vampire bat communities grew along with the cattle they fed on. After decades of ranching, landowners are converting pastures into more profitable sugar cane production—reducing food supply for the bats. At the same time, the number of feral pigs have been on the rise. Introduced to the Americas by European explorers, feral swine are an invasive species in Brazil. In the 1990s, large-scale commercial efforts to raise boar meat in Brazil failed, even after efforts to cross wild boars with domestic sows.

These boars are also found in 45 states in the US, and are also considered an invasive species. The animals, hunted for sport, may spread a bacterial infection, brucellosis, to hunters through handling or eating inadequately cooked meat.

In South America, ranchers eventually released their mixed herds into the wild. Vampire bats, with their food supply displaced, adapted to take advantage of increasing numbers of exceptionally fertile feral pigs. "Vampire bats are fond of pigs' blood, and switching from domestic to feral pigs must have been easy for such an adaptable animal," study authors noted in a press release.

Vampire Bats & Feral Pigs Together—A Recipe for Disease Emergence

Setting out remote-controlled infrared cameras with sensors, researchers were able to collect 10,529 images of bats feeding on a variety of wildlife include feral pigs, cattle, deer, and tapir (a plant-eating mammal similar to a pig, but with a prehensile nose). According to their survey, the probability of feral pigs being attacked on any given night along the Atlantic Forest of Brazil at approximately 11 percent.

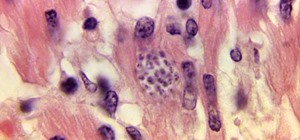

The numbers of bats and wild boar continue to increase, and, as carriers of disease, bats can infect their blood meal (the pigs) with infections they carry. This means each night, a viral chain of transmission is taking place that could impact humans.

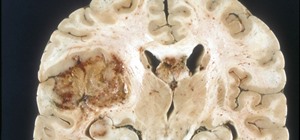

For example, bats can carry rabies—a fatal infection for animals and humans. While domestic livestock can be vaccinated for rabies, wild animals like boars cannot, raising the specter of a rabies outbreak.

With rabies and other infectious pathogens in their saliva, vampire bats bite wild animals later killed by bushmeat hunters. The hunters, who consume the meat, are exposed to bodily fluids, and occasionally bitten by bats, as are their dogs.

Beyond transmitting an already fatal disease like rabies, the mixing of viral pieces from different species could create an as-yet unknown virus that could be easier to transmit to humans than rabies. This melting pot of disease vectors and hosts leads to a description of the setting by researchers:

Human-induced changes in the environment are linked to an increasing occurrence of emerging infectious diseases, including spillover of viruses from bats to humans and other mammals.

With no remedy in sight, the continued mixing of dangerous microbes between hosts and carriers in South and Central America plays to the adaptive ability of pathogens. Time—and biology—will tell.

Just updated your iPhone? You'll find new emoji, enhanced security, podcast transcripts, Apple Cash virtual numbers, and other useful features. There are even new additions hidden within Safari. Find out what's new and changed on your iPhone with the iOS 17.4 update.

Be the First to Comment

Share Your Thoughts