What's in a sneeze? Quite a lot—dirt, mucus, and infectious germs—it seems. And sneezing the right way can reduce the germs you share with neighbors.

It's just a sneeze right? Everybody sneezes. So if you share a few germs when you are sick (or not sick), it's not such a terrible thing. Except when it is. Across the nation, five children have already died from influenza (the flu) this season. Every bit of unnecessary contagion you put out there can hurt someone else, especially if it is someone who is very young, older, or already ill.

Across the country, between 5% and 10% of Americans get the flu each year and we suffer more than one billion colds. How these viruses are transmitted, or how you "catch a cold," plays a big part in those numbers. Taking steps to protect yourself and others from getting sick makes sense.

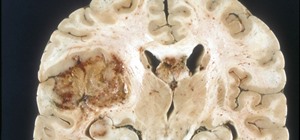

Sneezing is an efficient way to disperse germs. One sneeze can spew contagion across a room with velocity to spare. It's also forceful enough to create tiny droplets of mucous and germs that hang in the air, waiting to be inhaled. Let's take a look at the physiology of sneezing, what it does, and what you can do to stop it from doing anything to someone else.

Achoo! (Repeat)

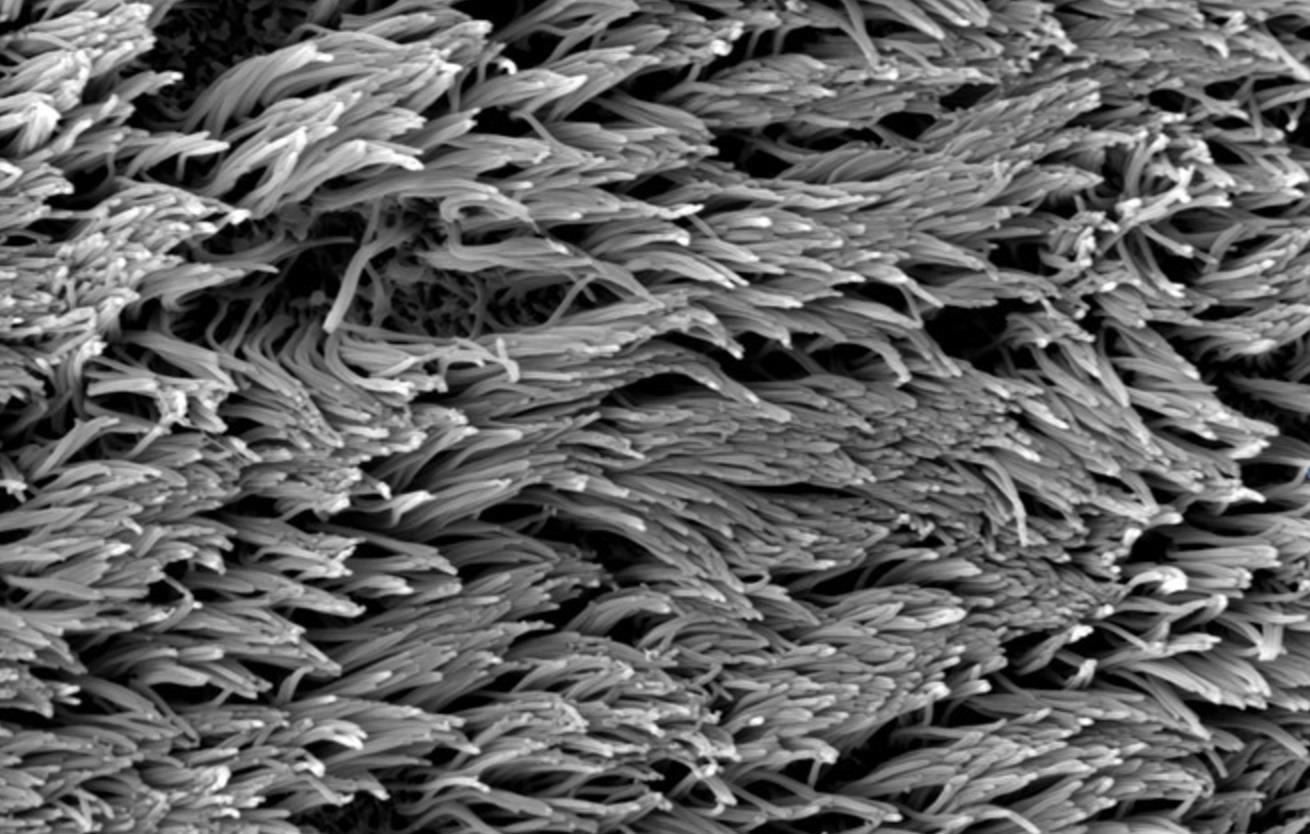

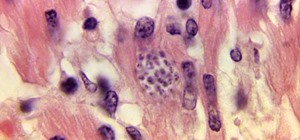

One of the really cool features of your nose and sinus passages is cilia. Rhythmically beating about 16 times a second, cilia are tiny hairs in you nasal passages seen only with a microscope. Your body uses nose hair, mucous, and cilia to defend you from viruses, pollution, bacteria, and other microbes.

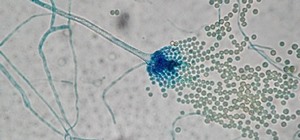

Nose hair and mucous are underappreciated. Your body produces about four cups of mucous a day to keep respiratory passages moist and gooey. Sort of like flypaper, this setup is a first-line defense against invading respiratory pathogens.

Despite what you may have heard, the color of your mucous, unless is it white and pus-like, is not a determinant of whether you have a viral or bacterial infection. Science says the green and yellow colors of mucous are influenced by the iron in enzymes produced by your white blood cells that help take out foreign pathogens. So—do not contribute to the superbug problem by insisting your doctor call in a scrip for a self-diagnosed sinus infection.

As you inhale, larger germs are filtered by nose hair, caught in the mucous, and swept along by cilia toward the throat, and away from your lungs, where they can meet their end in the stomach. Two other avenues for repelling microbes and particulate are coughing and sneezing.

When an irritant passes through nasal hairs, it may trigger a response from nerve cells that communicate with your brain. It is the reflex of a sneeze, the rapid filling of the lungs, and increased pressure caused by the tightening tracheal, facial, throat, and chest muscles, that forcefully propel air into the nasal cavity and out of the nose to clear dislodge the irritant.

Some people sneeze reflexively in the sun, or when tweezing eyebrows, possibly due to stimulation of the trigeminal nerve, a cranial nerve that branches through the face and is responsible for facial sensation, among other functions.

After a sneeze, the cilia are more active for a few minutes to clear nasal passages, and you may sneeze again. Sneezing very effectively expels germs by blowing them forcefully into space—sometimes 25 feet away.

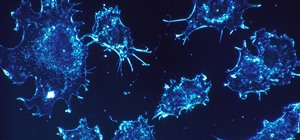

Avoiding a cold is important to you and your family, and it is also of interest to those who study disease transmission. While viral infections like Zika and Ebola are not known to spread through inhalation, influenza and rhinoviruses (the viruses most responsible for common cold symptoms) spread easily when aerosolized by a sneeze into the air.

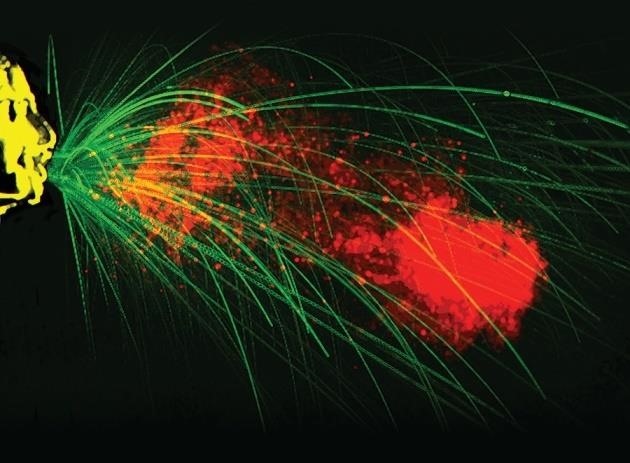

A sneeze expels small and large droplets of mucous, saliva, and pathogens, in the form of "turbulent buoyant clouds," according to researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The force and distance by which a sneeze carries infectious matter has implications for the vulnerability of any population or group of people in the event of an outbreak of influenza, or severe acute respiratory syndrome.

For relief, antihistamines block the production of histamines in your body, the compounds that cause your nose to itch and get "stuffy." Decongestants reduce the swelling and pressure too, improving your breathing, and reducing your inclination to sneeze.

Sneezing has its serious side, too. In 2014, a 17-year old British teen died after a short round of six sneezes that caused a fatal brain hemorrhage. For the healthy young man, Liam Andrews, it was a freak and tragic cause of death. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, the unfortunate record for the longest sneezing fit belongs to Donna Griffiths, a British woman who began sneezing on January 13, 1981, and finally had a "sneeze-free" day on September 16, 1983. In the first year, Griffiths sneezed approximately one million times.

The best way to sneeze without sharing your germs is to sneeze fully into the bend in your arm or shoulder, being sure your arm fully absorbs your sneeze. Sneezing into your hand, or even tissues, frees germs to fly. In any case, wash hands after you sneeze.

When you sneeze or cough, the germs you dispense can survive for a time where they fall. Most pathogens do not survive on soft surfaces, like carpet or fabric, as long as they can on hard, nonporous surfaces.

On hard surfaces, flu viruses can still live for hours or up to two days. Cold viruses usually die within the hour. Some bacteria, on the other hand, survive for months on hard surfaces. Temperature and humidity impact the hardiness of germs, and even a few minutes is long enough to catch a cold if someone else picks up or touches contaminated objects, surfaces, or breathes in your germs.

During any season, tips that can help you reduce the spread of colds and flu include:

- Clean and disinfect hard surfaces by washing and use of a household cleaner. When you clean, it removes germs. When you disinfect—it kills germs. Read the directions on your cleaner to be sure ingredients are safe for the surfaces you are cleaning, and are approved by the EPA for disinfection. Use disinfecting wipes for devices and cell phones. Make sure to follow directions to avoid damage to your electronics. Vinegar has disinfecting properties, but is not effective against Staphylococcus, a bacteria that commonly causes skin infections. Used full strength, vinegar is effective against Escherichia coli (E. Coli) and Salmonella typhi.

- Wash your hands with soap and water on palms, between fingers, and the back of your hands for 20 seconds. Use an alcohol-based sanitizer if soap and water are not available.

- Avoid touching your mouth, chewing fingernails, or rubbing your eyes to lessen the chance of infecting yourself with germs you pick up on surfaces.

- Steer clear of those who are sick if you can. If you are sick, do your coworkers a favor and stay home.

'Tis the season for colds and flu. There is action and a lot of other stuff packed into each sneeze. Remember to sneeze responsibly, and keep your germs to yourself.

Just updated your iPhone? You'll find new emoji, enhanced security, podcast transcripts, Apple Cash virtual numbers, and other useful features. There are even new additions hidden within Safari. Find out what's new and changed on your iPhone with the iOS 17.4 update.

Be the First to Comment

Share Your Thoughts