Several recent research studies have pointed to the importance of the microbes that live in our gut to many aspects of our health. A recent finding shows how bacteria that penetrate the mucus lining of the colon could play a significant role in diabetes.

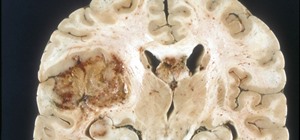

The new study led by Benoit Chassaing, Ph.D. and Andrew Gewirtz at Georgia State University found that microbes that encroach on the lining of the gut can produce chronic inflammation and that inflammation interferes with the normal action of insulin and promotes diabetes.

Their work was published online in April in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Our Gut Microbiome

Over 100 trillion microorganisms from 1000 bacterial species live in our gut and play roles in human physiology, metabolism, nutrition, and immune function. The bacteria that make up our gut microbiome, the community of bacteria in our gut, is determined by factors that include our environment, what we eat, and antibiotic use. Despite the variety of bacteria found in our gut, a few show up en mass and are considered indicators of a healthy gut microbiome. These healthy gut microbiota are bacteria of the phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes.

Disruption of the normal types of bacteria in the gut microbiome has been linked to gastrointestinal conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease. Researchers don't currently understand the reason for the association, but a clue may lie in the connection between bacteria and inflammation, a reaction of the immune system to foreign particles, such as bacteria.

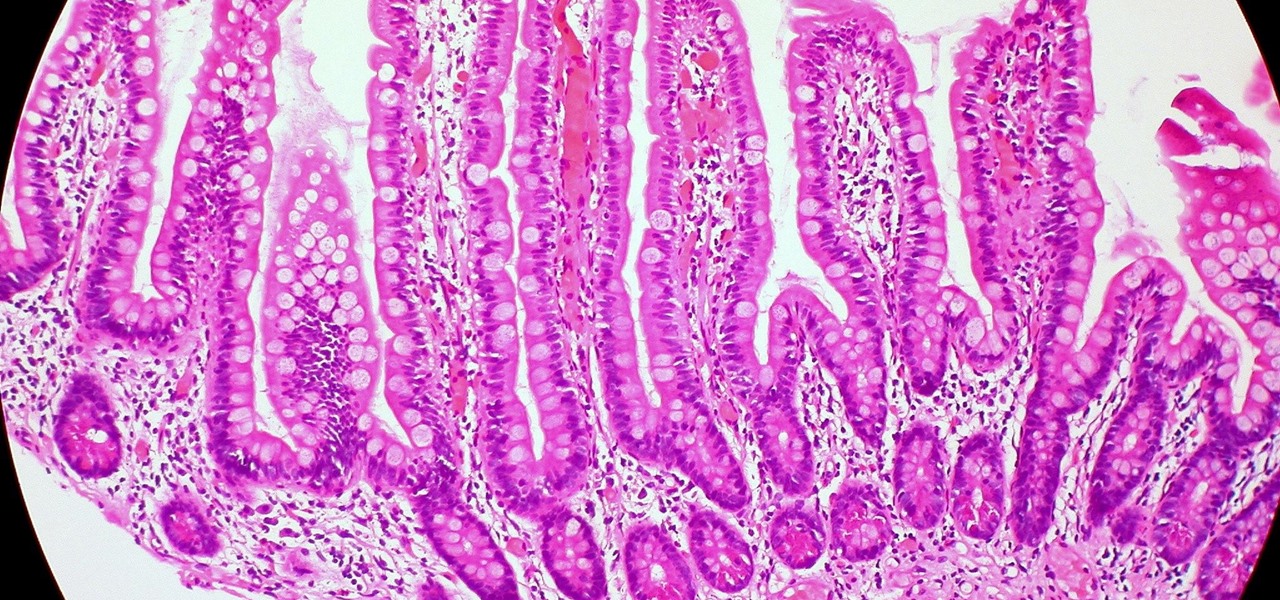

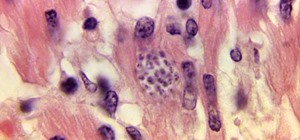

Mucus-producing cells cover the epithelial layer of cells that make up our gut wall and create a barrier, isolating the bacteria within the gut from the rest of the body. Chassaing and Gewirtz theorized that if gut bacteria broached the mucus-epithelial interface, they would cause inflammation and potentially promote diabetes, explaining the well-documented connection between inflammation, insulin resistance, and diabetes.

Diabetes-Gut Microbiome Link Found

The research team built on previous studies in mice showing bacteria can encroach upon the epithelium of the gut wall.

To investigate the relationship between diabetes and gut microbes, researchers studied people who were having a routine colonoscopy, a screening procedure for colon cancer. As part of the research study, the patients had two biopsies taken from the mucosal lining of their colon, which the researchers measured to determine how far the gut bacteria had encroached upon the gut wall, a measurement called the "microbiota-epithelial distance." They also tested these biopsies for the presence of immune cells.

The average age of the study participants was 58, 86% were overweight with a body mass index of 25 to 30, 45% were obese with a body mass index of 30 or higher, and 33% had diabetes. The researchers also tested the patients' blood sugar and hemoglobin A1C levels — an indication of a person's average levels of blood glucose.

The researchers saw an inverse correlation between microbiota-epithelial distance and measures of metabolic syndrome: body mass index, fasting blood glucose levels, and hemoglobin A1C concentrations. The lower the patient's microbiota-epithelial distance, the higher measures of metabolic syndrome. The researchers saw the gut microbiota encroaching on the epithelium in overweight diabetes patients whose bodies were less in control of their blood sugar.

Two of their findings were unexpected. One was that that obesity alone — without diabetes — was not correlated with encroachment. Encroachment was seen in obese patients only if they also had diabetes.

The researchers also found a link between microbiota encroachment in patients with diabetes and an increase in CD19 B cells of the immune system. In other studies, the presence of CD19 B cells correlated with improved gut health in patients with celiac disease, a digestive disease where consuming gluten damages the intestine through a misfiring immune response.

At this point, the authors don't know if the CD19 immune cells are beneficial, as they are in celiac, or if they are brought on by the inflammation caused by encroaching gut bacteria. They suggested that the finding of B cells in cases of bacterial encroachment may hold the key to the nature of the connection between diabetes and inflammation.

"Previous studies in mice have indicated that bacteria that are able to encroach upon the epithelium might be able to promote inflammation that drives metabolic diseases," Gewirtz said in a press release. "Now we've shown that this is also a feature of metabolic disease in humans, specifically type 2 diabetics who are exhibiting microbiota encroachment."

This study reveals a new connection between gut bacteria, diabetes, and inflammation. There's a lot left to explore and many more questions to answer. For now, the team is conducting studies to identify which types of bacteria invade the mucosal lining and are looking for ways to prevent the bacterial encroachment.

In the long term, we need to continue to focus attention on the role of our gut in health and disease conditions. Reinforcing that focus is another important finding of this study.

Just updated your iPhone? You'll find new emoji, enhanced security, podcast transcripts, Apple Cash virtual numbers, and other useful features. There are even new additions hidden within Safari. Find out what's new and changed on your iPhone with the iOS 17.4 update.

Be the First to Comment

Share Your Thoughts